Riddle of Varying Warm Water Inflow In the Arctic Now Solvedhttps://phys.org/news/2023-09-riddle-varying-inflow-arctic.html

In the "weather kitchen," the interplay between the Azores High and Icelandic Low has a substantial effect on how much warm water the Atlantic transports to the Arctic along the Norwegian coast. But this rhythm can be thrown off for years at a time.

Experts from the Alfred Wegener Institute finally have an explanation for why: Due to unusual atmospheric pressure conditions over the North Atlantic, low-pressure areas are diverted from their usual track, which disrupts the coupling between the Azores High, the Icelandic Low and the winds off the Norwegian coast. This finding is an important step toward refining climate models.

... A team led by oceanographer Finn Heukamp from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) has just published a study in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, in which he and his colleagues investigated ocean currents along the Norwegian coast and into the Barents Sea. Their focus was on the atmospheric pressure difference between the Azores High and the Icelandic Low, also known as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which shapes the currents off of Norway.

They were particularly interested in the question of why there are (in some cases, extreme) deviations from the typical interplay between the NAO and weather conditions. Normally, the intensity of the winds and therefore the ocean currents is predominantly determined by the atmospheric pressure difference in the NAO.

When the NAO is more pronounced, it creates powerful air currents, which drive low-pressure areas across the North Atlantic and past Norway on their way north. When the atmospheric pressure difference lessens, both the winds and the low-pressure areas run out of momentum.

As such, the NAO, the low-pressure areas' track, and the intensity of the ocean currents off the coast of Norway are normally closely interconnected. However, a decoupling of the NAO and ocean currents was observed in the Barents Sea as far back as the late 1990s.

"This unusual decoupling frequently manifested in winter between the years 1995 and 2005," says Heukamp. "But the cause of these changes was unclear." Thanks to a mathematical ocean model that simulates the Arctic Ocean at very high resolution, the experts now have the answer.

Apparently, the phenomenon is caused by an unusual change in the low-pressure areas' track. Heukamp has now determined that the stream of low-pressure areas that pass by Norway, moving from the southwest to the north, is at times disrupted by powerful, nearly stationary high-pressure areas, also known as blocking highs. The latter push the fast-moving low-pressure areas out of their normal track. As a result, the NAO and the northward flow of warm water are temporarily decoupled.

"Global climate models simulate on a comparatively broad scale," the researcher explains. "With the latest results from our high-resolution analysis for the North Atlantic and the Arctic, we've now added an important detail for making climate modeling for the Arctic even more accurate." They also show that, in future, the NAO, the low-pressure areas over the Atlantic, and the ocean currents need to increasingly be viewed together.

Given that both the transport of warm water and the track of lows over the Atlantic affect our weather in the middle latitudes, the results are also interesting in terms of more accurately predicting the future climate and weather in Central Europe.

Finn Ole Heukamp et al,

Cyclones modulate the control of the North Atlantic Oscillation on transports into the Barents Sea,

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

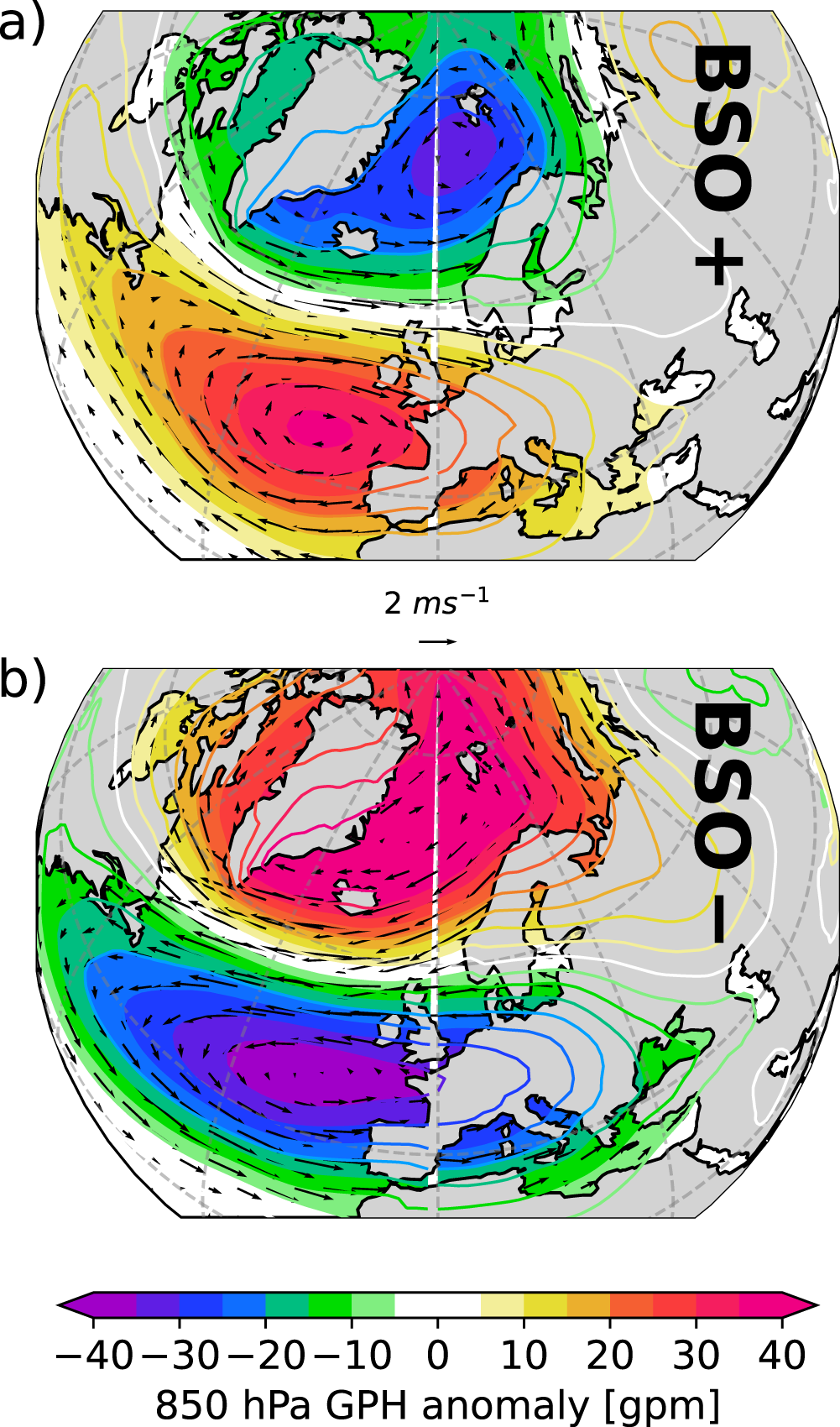

https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-023-00985-1 Composite maps of 850 hPa geopotential height anomalies and associated wind anomalies (DJFM) during strong (a) and weak (b) net transport through Barents Sea Opening (BSO) based on JRA55.

Composite maps of 850 hPa geopotential height anomalies and associated wind anomalies (DJFM) during strong (a) and weak (b) net transport through Barents Sea Opening (BSO) based on JRA55.